How do you explain desegregation to children? How do you explain that schools were once segregated by race? We had never talked about racism with the girls before. They don’t ever say much about anyone’s race, other than sometimes describing a person as having dark brown skin, tan skin, peach, or light skin.

They learned about Martin Luther King, Jr. in Kindergarten last year, but that was limited to songs about him wanting peace for all people.

They know what bullying is and that when people are ugly to others because they are different from them, it is wrong. When we explained that white kids and black kids went to separate schools many years ago, we were met with lots of questions. It’s pretty hard to explain why people were kept out of places because their skin was darker.

“Why? Because their skin was brown? But why?”

“Um, people were afraid of people who were a different color than them…? They didn’t want change. It was sort of like bullying… They thought it was best to stay separate.”

Looks of confusion.

This discussion prefaced our visit to a National Historic Site this afternoon. Today we went to visit Little Rock Central High School, which is still an operating school, but also has major historical significance.

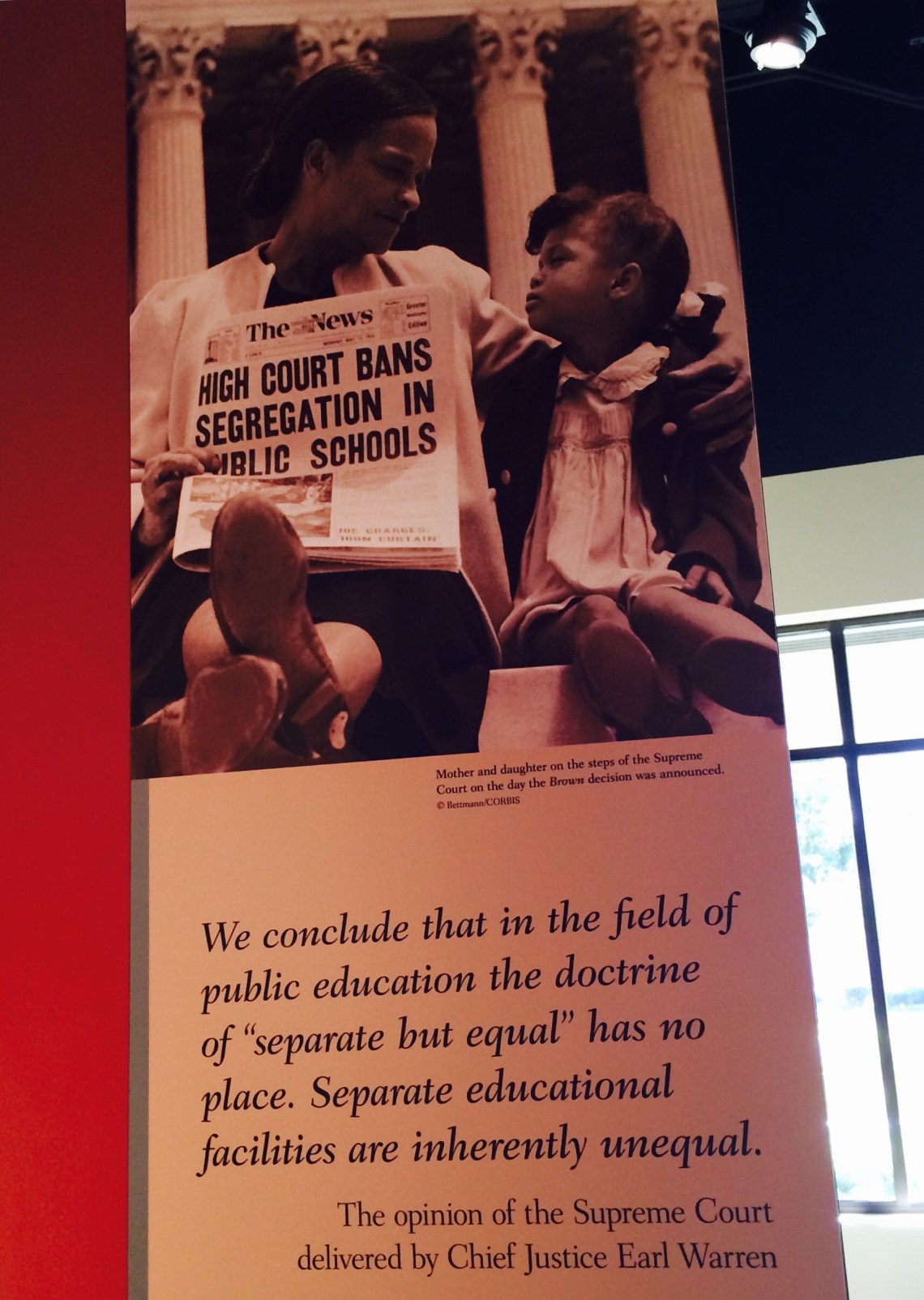

In September of 1957, as part of the Little Rock School Board’s plan to gradually integrate schools, nine African American students were enrolled in Central High. This led the Arkansas governor at the time to invoke “states’ rights,” claiming that The Supreme Court had overstepped boundaries with Brown v. Board of Education. He was strongly against integration in his state. What followed was nothing short of a national embarrassment.

By order of the governor, the National Guard kept the Little Rock Nine from entering the school on their first day. After a federal ruling was handed down a couple of weeks later saying the Guard could not do that, police were ordered to protect the Nine as they entered the school. The police couldn’t protect them, though. Angry mobs and rioting sent the Nine out a side exit of the school to a police car, fleeing danger.

Following that, President Eisenhower sent 1,200 soldiers to protect the Nine as they went back to school. The governor then ended up closing schools altogether at one point, until federal court deemed the closings unconstitutional, and school returned to session. Several of the Nine later graduated from Central High.

Our visit began with a stop at the museum, which was helpful, because we were able to watch videos, look at timelines, and read some of the history to the kids. They also received workbooks, where they could answer questions like, “How would you feel if you had to be escorted into school by a soldier because of the color of your skin?”

“Sad. Scared.”

The nice thing about homeschooling is learning can happen in many different places and in many different ways. Sometimes it can involve a lesson from a park ranger, a museum visit, and a walk over to a place where history was made – which is what we did next.

The school is just across the street from the museum, so we took the short walk over. It’s a gorgeous building. The architecture is stunning. Busses were lined up waiting on the current students, as it was just after 3 p.m., and the school day was ending in about 45 minutes. I thought about waiting for the school doors to open and the kids to rush out. It would be kind of cool to witness a sea of different shades of kids emerge from the building and descend the steps where those Nine made history almost 60 years ago. But we didn’t wait; we took our pictures and headed on.

Though I don’t know how good of a job we did explaining all the events that took place at this spot in Arkansas so many years ago, I was pretty happy to find a children’s book on the Little Rock Nine at the gift shop that the girls can read later. I’m sure it will do a much better job of telling the story.

* On a side note, the girls were sworn in as Junior Park Rangers.